I can already tell this will be one of my top reads of 2024.

In my recent review of The Last Tsar’s Dragons, I mention that “despite sustained interest in Russian history, culture, religion and mythology my knowledge of the Romanov family before reading {that} book was pretty limited . . .”

I would say the same is true for post-Tsar Russia as well.

Of course certain names are likely to be remembered from even the broadest (ahem rudimentary) education. Nicholas II, Rasputin, Stalin, Lenin, and (especially) these days . . . Vladimir Putin.

But how about Lavrenty Beria (leader of the NKVD in 1953), Yuri Gargarin (Soviet Cosmonaut), or Boris Yeltzin (president of Russia before Putin’s first time)? Assuredly these names are lesser known here in the west, or at the very least lesser known in modern times (I wonder how much more familiar these names would be to my parents or any Gen Xers). But they were each important in shaping the Russia we know today . . .

And all these important people had to eat!

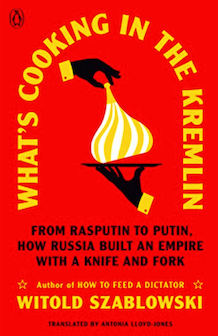

This is where What’s Cooking in The Kremlin‘s primary focus lies, in telling the story of the chefs and cooks who kept history fed.

I liked this approach for several reasons. First I think it makes the history a bit more accessible. There is something intimate about a person’s diet that really makes them human. No longer just a name to memorize, or a myth to remember.

Second, hearing the stories of these incredible chefs, in many cases in their own words, really just opened up the culture for me in a way that I don’t think another book could have accomplished. For instance, reading the words of a tour guide at the dacha Lenin spent his final days in, you can really hear the regard with which some Russians still hold him, and perhaps by extension, communism too. Contrast that with the words of a shoemaker turned cook in Afghanistan, or refugees in Crimea, or a survivor of the famine in Ukraine who have no illusions (or none any longer) about ‘The Party’.

I think the author did a good job handling a range of subjects, mixing many facets of history together. Stories about what the cosmonauts ate on the first trips into space were actually quite awe inspiring, while obviously stories about surviving the famine in Ukraine, or the siege of Leningrad were humbling in the extreme.

And then of course there was all of the little details that the book was not ‘about’, but still provided such a unique and interesting picture that you could not help but soak them in. That Stalin’s food taster, Alexander Yakovlevich Egnatashivlili, was called krolik which literally means rabbit, but is used like how we would use the term guinea pig. That (in general) cooks are always under suspicion of stealing, but that it’s also good to have a cook in the family because it means you’re unlikely to starve. And of course, all the many Russian proverbs. One in particular — “To pluck a little from a lot isn’t stealing. It’s fair distribution.” — stuck out to me as perhaps very telling.

But What About the Food?

There was tons of it. Churek, and Kulish, and Salo. Tvorog, and Bigos, and Zazharka. Every page seemed to be filled with the description of some new (to me) dish and often some historical or cultural significance applied to it. And plenty of dishes were not explained at all but familiarity was just assumed (still wondering how does one prepare sturgeon “monastery style”?).

I took sooo many notes about these little (ahem) morsels, and loved to discover them, but obviously the main draw was the actual recipes included within the text. I was really looking forward to trying them out, and forming some kind of connection to these stories that was deeper than just reading . . . that was also tasting and eating.

Unfortunately, I think this was the only part of the book that let me down. I’m not much of a cook, and the recipes within were in many cases quite difficult (or as one of my friends said “the recipes are just vibes”). When cooking for the Tsar, or the President of all of Russia, exotic foods like a specific type of quail (maybe now extinct), or a freshly hunted boar, are not far-fetched, and cool to see how one might handle cooking that however unlikely it would be to actually do it.

But some of the recipes for more common foods also seemed needlessly vague or difficult to reproduce. I tried making Shchi (a kind of cabbage soup), and got about halfway through cooking it before I realized that following the recipe exactly was actually not helpful in the slightest.

It could just be that I’m inexperienced, and a better cook might have had an easier time, but I unfortunately was not up to the task.

Give this One a Read?

Despite my difficulties in the kitchen I had a tremendous time reading this book. I cannot say that all of the topics covered within are roses and sunshine, in fact, mostly they are not, but the stories told here are powerful and deeply meaningful anyway.

If you’re looking for something a little different, I highly recommend this one.

That’s all I have to say for this week. Has anyone read this one yet? What were your thoughts? Do you have a favorite Russian dish? Let me know in the comments.

Until next time . . .